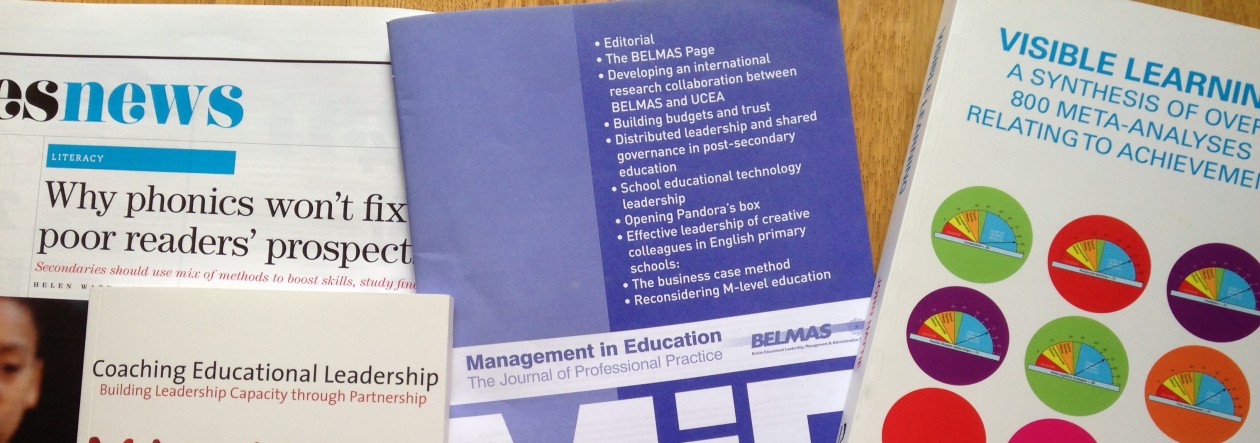

Professor John Hattie’s Visible Learning came well before ‘What makes great teaching’ (Sutton Trust). The two should be having a great impact on the way approach our work.

Hattie’s ‘What doesn’t work in Education’ (June 2015) adds important detail to research evidence and goes a long way to explain why some strategies don’t work.

He talks about the Politics of Distraction.

Distraction 1: Appease the parents

Are too many policies aimed at appeasing parents? For example, reducing class sizes is a strategy that pleases parents, teachers and school leaders. Parents see reducing class size as a sure-fire way of more attention being paid to their children. Teachers see it as stress reducing (less marking?) and leaders consider it beneficial to stretching resources. But as Hattie points out, whilst the positive effect of smaller classes does exist, it is very small. Why? Because too many of us rarely change how we teach when we have a smaller class. In fact Hattie’s 2005 work found that we often talk more in a smaller class!

Have a look at fig 4.1 on p11 of the report and note the reading ages of two countries with highest reading ages.

Distraction 2: Fix the infrastructure

One of the major distractions to truly making a difference is the quest for better infrastructure: a more effective curricula, more rigorous standards, more tests and more alternative shaped buildings, etc.

Hattie refers to ‘tinkering with the curriculum’. This is interesting. It is copied directly from p15 of the report:

When you are learning something new, you need a greater proportion of surface to deep thinking, but as you become more proficient, the balance can change to more deep thinking. Consider, for example, the following seemingly sane and sensible teaching programmes privileging deep learning:

• inquiry-based learning;

• individualised instruction;

• matching teaching to styles of thinking;

• problem-based learning;

• whole-language learning; and

• student control over learning.

The average effect-sizes of these programmes are very low (0.31, 0.22, 0.17, 0.15, 0.06 and 0.04 respectively), well below the average of many possible influences of 0.4. It is not that they are not worthwhile programmes. The problem is that too often they are implemented in a way that does not develop surface understanding first. (My bold italics. This is the essence of the work)

The section on buildings is fascinating and easily recognisable. Changing the shape of the teaching space does not lead to us teaching differently. He gives the example of teachers filling open plan spaces with bookcases and trees in pots to create their own ‘walled in spaces’.

Distraction 3: Fix the students

‘During a child’s first five years, there is remarkable brain development. They can learn so much, and there are so many opportunities to enhance their learning. Thus, there has been a focus in many systems on providing early childhood education systems. However, the robustness of classifying students is questionable.’ (p19)

Because of this, vast sums of money are poured into early years. Yet it is pointed out that by the age of 8, it is hard to tell who did/ didn’t have pre-school education.

Distraction 4: Fix the schools

‘A popular solution to counter ‘failing schools’ is to invent new types of schools: charter schools, for-profit schools, beacon schools, free schools, academies, public–private schools – anything other than a [state maintained school]. But, given that the variance in student achievement between schools is small relative to variance within schools, it is folly to believe that a solution lies in different forms of schools. Within a year or so the ‘different’ school becomes just another school, with all the usual issues that confront all schools.’ (p23)

Distraction 5: Fix the teachers

“The system is only as good as the teacher and that teacher standards must be raised.” A well recognised mantra. There is nothing wrong with this but we can’t do it all on our own: we need support, to collaborate with others in and across schools and to develop expertise This is unlikely without excellent school leaders. Further, supportive and great systems are needed to support and nurture great leaders. “But more often the debate is about … introducing performance pay and other such distractions.”